Key Takeaways

- Strong business cases connect ideas to organizational goals—without them, even great projects can be dismissed.

- Effective business analysts frame problems clearly, justify investments, and present actionable, well-supported recommendations.

- A reusable business case process builds trust, speeds up approvals, and prevents costly project delays.

When Strong Ideas Hit a Wall

A cross-functional team proposes an innovative solution to speed up onboarding. Everyone agrees it’s needed, the technology already exists, and yet the answer from leadership is still no. There’s no business case showing costs, benefits, or how it supports broader goals. Without a clear process in place, the project dies before it starts.

Even with strong leadership and technology in place, without the right process to guide decisions, project momentum can stall. Business Analysts (BAs) are expected to connect ideas to outcomes. Their role is to show why an idea matters, how it solves a problem, and what value it brings. That’s precisely what a business case does. It bridges the gap between an idea and an approved initiative.

Here’s how to build one that earns buy-in, avoids costly delays, and sets your team up for impact.

Why One Document Can Make or Break Your Next Project

Business cases give BAs a straightforward way to connect good ideas to organizational priorities and long-term goals. Without one, even well-planned initiatives can be dismissed as unclear or misaligned.

A strong business case does the following:

- Justifies investment in a project, product, or solution

- Compares alternatives and outlines expected benefits

- Aligns stakeholders on goals, value, and feasibility

- Serves as a guide for decision-making and funding allocation

BAs should lead whenever a project involves:

- A significant cost, time, or resource investment

- Input or impact across multiple departments

- Competing priorities that require leadership to make tradeoffs

Without processes, even strong leadership and advanced tools fall short. A business case ties them together, starting with how the problem is framed.

If You Can’t Explain the Problem, You’ll Never Get Approval

One of the most important contributions a Business Analyst makes is defining the problem so it is focused, measurable, and urgent. A vague explanation leads to hesitation, but a clearly defined issue backed by context builds confidence that leadership is addressing the right challenge.

A strong opening should include:

- A concise problem statement or opportunity description

- Background context about what’s happening and why it matters now

- The risk of doing nothing (status quo consequences)

- Unmet needs or pain points from stakeholders

- Evidence from data and stakeholder input to confirm the problem is real and worth solving

Here are some examples of strong opening lines:

- “Customer onboarding takes 10 days longer than our top competitors.”

- “Manual reporting is costing 20 hours of analyst time every week.”

In the onboarding example, the BAs saw they were behind industry standards. Delays frustrated customers and tied up internal teams with manual follow-ups. Framing it as both a competitive gap and internal cost made it clear this was a business risk, not just an inconvenience.

Clear problem framing gives leadership the urgency and focus to act. With a well-defined challenge, the next step is shaping a solution that leaders can support. Strong cases also link the problem to organizational goals to show how solving it advances strategy.

What Smart Business Analysts Do Before Leadership Pushes Back

A well-framed solution shows leadership that BAs are not making guesses. It means clearly outlining the scope and assumptions. It impacts in a way that builds confidence; the process is both structured and transparent.

Clarity matters. A strong outline defines the plan, exclusions, and ownership to prevent scope creep. It includes key assumptions, impacts, and dependencies. BAs should tie the solution to strategic goals and tailor messaging for each audience. Early planning avoids blind spots, and a pilot helps validate assumptions.

In the onboarding example, BAs proposed a self-service portal for sign-up, document upload, and status tracking with Salesforce integration and later marketing automation. They aimed to reduce onboarding emails by 50 percent and planned a pilot to test the approach. Marketing would save time, while IT would take on more support during rollout.

Use a format like this to bring structure to the proposal:

| Item | Description |

| Proposed Solution | Implement a self-service customer onboarding portal |

| Scope | Sign-up form, ID verification, document upload |

| Constraints | Must connect with existing Salesforce workflows |

| Assumptions | Portal will cut onboarding emails by at least 50 percent |

| Stakeholder Impact | Marketing saves time; IT sees more support requests |

| Assumption Testing | Pilot the portal with 50 customers and track email volume |

Addressing scope, impact, and assumptions early helps reduce friction later. When BAs take time to define their solution and boundaries clearly, they make it easier for leadership to focus on value. That clarity sets the stage for weighing costs, benefits, and tradeoffs with confidence.

Don’t Ask for Approval Without Cost Estimates

Leaders want to know not only what a project will cost but also what it will return and when. Technology aids in forecasting, and leadership provides support; however, without a structured process, decisions often stall. A clear business case brings that discipline into the conversation.

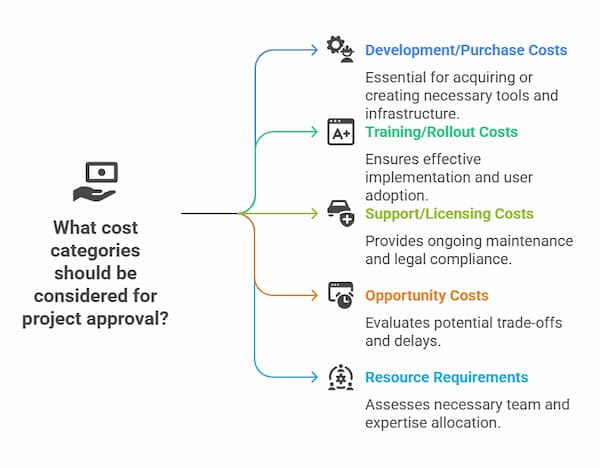

Common cost categories include:

- Development or purchase costs

- Training and rollout

- Support or licensing

- Opportunity costs (what gets delayed to make room)

- Resource requirements (team time, expertise, and availability)

Common benefits include:

- Time or cost savings

- Revenue growth

- Risk reduction

- Compliance or strategic alignment

- Intangible benefits such as customer satisfaction or employee morale

Make sure to include:

- Which team members are needed and how much time they’ll need per week or phase

- Any skill gaps that could slow progress, and whether support is internal or external

- How much change the organization can handle, based on current workload and recent changes

- What success looks like, including KPIs, who tracks them, and how often they’re reviewed

For the onboarding portal, BAs estimated $40,000 for development and integration, with savings of 15 hours per week, improved customer satisfaction, and fewer handoffs. They planned for a learning curve and added IT and Customer Success support for the first 60 days, giving leadership a clear view of the investment and return.

Conservative estimates build trust. BAs boost credibility by analyzing tradeoffs and offering realistic projections. A solid financial case enables leaders to compare priorities, manage risk, and allocate resources to the right initiatives. Linking benefits to strategic goals or OKRs shows alignment. With processes to track impact and adapt, the business case becomes a reusable tool—not a one-time document.

With costs and benefits clear, leadership also expects to see what alternatives were considered and how risks will be managed.

Why Leaders Won’t Buy In Without Options and Risks

Leadership wants to see that alternatives were considered and that BAs selected the most viable approach based on real tradeoffs. This means showing the options that were weighed and the risks that were identified.

BAs should explore alternatives like:

- Doing nothing (status quo remains)

- Implementing a partial solution

- Buying a product versus building internally

- Outsourcing the work versus keeping it in-house

Risks should also be made clear. These may include:

- Implementation delays

- Cost overruns

- Resistance to adoption

- Vendor performance or reliability concerns

For each risk, include a practical plan to reduce its likelihood or limit its impact. If user adoption is a concern, it may be necessary to conduct user testing, provide targeted training, or assign change champions within teams to facilitate adoption. For cost overruns, consider a budget buffer or phased funding tied to key milestones. Assigning a clear owner for each risk also ensures accountability and follow-through.

BAs ruled out an off-the-shelf solution due to missing Salesforce integrations and dismissed a manual option, as it offered no time savings or experience improvements. To offset potential IT delays, they proposed a part-time contractor. These details showed the leadership that the BAs had weighed tradeoffs and planned.

When BAs demonstrate that alternatives were considered and risks planned for, they show leadership that the proposal is credible. This level of preparation naturally builds trust and sets up a recommendation that leaders can support.

How to Make a Recommendation That Gets a Yes

The recommendation is where all analysis comes together, and the Business Analyst guides leadership from options to a clear decision. Decision-makers want a summary that is confident, clear, and logically supported, paired with a one-page executive summary that highlights the problem, solution, costs, benefits, and risks, as many leaders read this first.

A strong close includes:

- The preferred solution and why it was selected

- A summary of expected benefits

- The most critical risks and how they’ll be managed

- Next steps or approvals required

- Key milestones and a high-level timeline

- Governance structure, including decision-making authority, escalation paths for significant changes, and how project progress will be reviewed across phases (e.g., checkpoints with steering committees or executive sponsors)

Use direct language. For example, “We recommend implementing the onboarding portal because it addresses current delays, reduces manual work, and can be piloted with minimal risk.”

In the final presentation, BAs recommended piloting the onboarding portal with 50 customers in the next quarter, measuring results against a 50 percent email reduction goal, and using the findings to determine whether to proceed with a full rollout. Governance was structured with Customer Success managing daily progress and IT providing oversight on system integration.

A clear recommendation turns analysis into action and makes leadership more likely to approve the work ahead. This final step connects all parts of the business case and establishes the broader context of why the best BAs never skip it.

Why the Best Business Analysts Never Skip the Business Case

Business cases aren’t just paperwork. For BAs, they’re strategic tools that show value, align leadership, process, and technology, and elevate their role from order-taker to trusted advisor. Without this structure, strong ideas often get shelved. Thoughtful business cases bridge the gap between opportunity and action.

A strong business case informs decisions, prevents misalignment, and creates accountability across teams. In complex organizations, this clarity is often the difference between stalled projects and meaningful results. Business cases are also essential at the portfolio level, where leaders must compare multiple initiatives and decide which to prioritize.

At Watermark Learning, we help BAs master business cases through expert-led training in analysis, stakeholder engagement, and strategic communication. Our instructors go beyond theory, offering practical tools and real-world insight to help BAs earn leadership support and move key initiatives forward.

Watermark Learning helps your BAs build the skills not just to present good ideas, but to drive them through to approval and impact.

Jay Pugh, PhD

Dr. Jay Pugh is an award-winning leader, author, and facilitator with over 18 years of teaching and training experience. Currently serving as Head of Leadership Growth at Educate 360, he leads a robust team of external and internal facilitators who specialize in developing leadership capabilities within medium and large-scale businesses. His team works directly with business professionals, helping them become more effective leaders in their daily operations.

Dr. Pugh holds a Ph.D. in Instructional Management and Leadership, and his academic contributions include two published articles and a dissertation focusing on various educational topics. His extensive experience and academic background have established him as a respected voice in leadership development and educational management.

New Horizons

New Horizons

Project Management Academy

Project Management Academy

Six Sigma Online

Six Sigma Online

Velopi

Velopi

Watermark Learning

Watermark Learning

Login

Login

New Horizons

New Horizons

Project Management Academy

Project Management Academy

Velopi

Velopi

Six Sigma Online

Six Sigma Online

Watermark Learning

Watermark Learning